Before “Think Different” there was “Think Black”…

Here in the rasx() context it looked like my friend, Dr. Margo Natalie Crawford, pulled a Sister Wendy and vanished (from my life) for years to meditate in solitude about the Black Arts Movement. So it turns out I am wrong about this on many levels (especially about the solitude)—nevertheless she has ‘returned’ from the peak of a sacred mountain of research with veritable tablets of stone (okay—silicon packed with silica: she does have an iPad) and is blowing me away. —And folks she needs our terrible help, with a little ditty called, In Our Terribleness—more on this later…

Before you can help her she has to help you. You have to get into the intellectual and historical framework that was the Black Arts Movement. From jump that means most of you 21st-century readers have to remember a time before digital devices—a time before personal computers. Simultaneously, you have to imagine an intellectual/creative space that was clearly preparing itself for the digital interactively we now take for granted. You see, kids, when you have a Black Arts Movement you have a political context filled with civil-rights-era self-determination. So there was no expectation that the audience would sit back passively like posh lords and ladies. The audience was meant to interact to activate with the artist and the artifact(s). In the mega-official-legally-racist zeitgeist of the time, to think like this was to “think Black”—to have these expectations about such interactive art in the mean streets of North America was considered a Black thang.

It can be hard to accept this because, for example, North Americans now commonly say the word “cool”—even in highly professional and technical situations (I first noticed this in the late 1990s with Microsoft people). But, kids, “we” tend to forget that, just before the Black Arts Movement was jumping off, to say the word “cool” meant you were a jazz hipster. It was an “animalistic,” “nigger thing” to say the word cool you dig? Now “everybody” says the word cool. So when Margo Natalie Crawford showed me that Black Arts Movement slogan “think Black” I immediately thought of the Apple advertising slogan meant for “everybody”: think different.

Crawford, her research, makes it clear that the word Black for many black-light luminaries of the Black Arts Movement meant more than just describing the cartoon-physical outcome of African descent in North American colonialism. Black for Black Arts folks meant turning the energy-inefficient lights out on oppressive conventions, stiff-square bullshit. Blackness was meant to be that void of newness—that “clean slate” that is so clean that a white sheet of paper is too much of an assumption. Now that white-lab-coat science tells us that human-eye visible matter only makes up four (or less) percent of the entire motherfucking universe we can (not) see how the word Black can mean starting from scratch—from the Dark Matter of all that is…

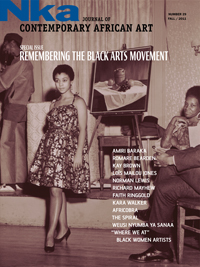

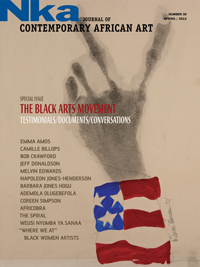

So dig: the artifact of primacy that introduces us to these Black Arts moves is the original edition of In Our Terribleness by Amiri Baraka with photography by Fundi Abernathy. In issue 29 (fall 2011) of Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, in her essay, “BlaCk aesthetiCs UnboUnd,” Crawford writes:

One of the movement’s most dramatic examples of the hailing of ideal black readers was the textual production In Our Terribleness (1970), by Amiri Baraka and the Chicago photographer Fundi Abernathy. The book begins with a full- page mirror image that demands that readers see their face as they enter this “long image story in motion”; the title, In Our Terribleness, is inscribed on this face.

Here in the rasx() context, the purpose of this book with a “counter-mirror” is to introduce interactivity between the user/reader and the makers of the book. Crawford writes:

The title page includes a silver mirror surface (apparently pasted in an intentionally homemade manner) with the words In Our Terribleness engraved in the center. The Black Arts movement shaped the reading of the black book into ideal black readers’ process of imagining that they were looking into a countermirror, a mirror that countered a dominant, hegemonic lens—the white gaze.

This vector of activism travels through the pages of the book. This object is meant to be a component of a larger “black body”—Crawford explains:

The black book incorporates the black body. We see this same emphasis on the intertwining of book and body when Baraka writes gesture on the right-hand margin of one page. The word appears at the very edge of the page, where readers would turn it. The black book not only hails black readers but also incorporates their bodily gestures.

Just in case the irresistible urge to simplify non-mainstream intellectualism with crudities kicks in, it must be mentioned that this “black body” is not the Black-1970s equivalent of Oral Robert’s 900-foot white Jesus (from 1977). We must remember this ‘larger’ meaning of blackness:

The editors, Larry Neal and Amiri Baraka, through their foreword and Neal’s afterword, move from the call for black nation building and liberated minds to Neal’s celebration of the space created by the destruction of double consciousness. Neal labels the undoing of binaries “Black.” There is a fundamental difference, in this anthology, between the setting of boundaries between black and white and Neal’s final move to a celebration of an aesthetic that blackens the boundaries between self and other, black and white. The blackening of this boundary crossing is easy to miss in quick and easy interpretations of the movement. Through the lens of Neal’s afterword, to “think black” is to deconstruct fixed identity and normative categories. In other parts of this anthology, to “think black” is to be most fixed and categorized. The unpackaged aspects of the Black Arts movement emerge when we zoom in on the contradictions in these most literal packages, the anthologies.

Yes, I know the following exercise renders hackneyed but: had Amiri, Larry and Fundi dropped In Our Terribleness today it would be an iPhone app—or an iTunes album. (No one would like such an app because it has blackness all over it—which is “so not cool” but… anyway…) In Our Terribleness was yearning for interactivity—“yearning” in the bell hooks sense of the word. Our most interactive, mass media at the moment is the digital.

So dig: Dr. Crawford would like you to revisit In Our Terribleness through the digital image. Do you remember reading In Our Terribleness? Are you one of the OGs that experienced the first edition back in the day? Then please, please send in a photo—a self-mirror-portrait of your Black-lit view into In Our Terribleness. Margo Natalie Crawford (who is quite an excellent poet, by the way) is working on a collaborative, interactive project that will showcase our “terrible” work. Send a Tweet to @KinteSpace.