About the cover photography of my first chapbook…

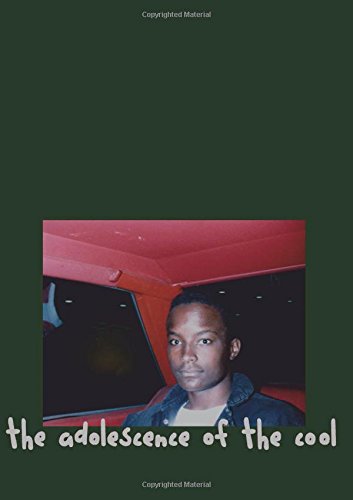

My mother took the photo on the cover on my first chapbook, the adolescence of the cool. And the first person who would not consider my mother a photographer would be my darkroom-building father. In that sense, the photo is an anti-photograph for anti-book cover. From a professional book marketing perspective, the cover I designed for my chapbook is a bricks-and-mortar retail disaster.

The first problem is the dark-colored “nothingness” that is the top third of the book. There is no author name, no title, no arresting image. It is doomed to sit on the shelves overlooked. This is exactly what I want to communicate because—for most of my relatively-incredible, Black-American life—I have been that overlooked dark color just sitting there (and I am talking about everyday interactions with everyday people). I do not make this statement for pity or sympathy because I can tell you from Blues-experience there is none.

What my father would find very, very difficult to do (because he is so formal, professional and technical) is capture a real, slice-of-life moment. What my mother did with ease in the photo is capture a moment in my life from my youth that even I would forget about were it not for her motherly intrusiveness.

I am sitting in the back of her 1979 Ford Fairmont. She is about to give me this car. But for one last time I am sitting in the backseat like her sheltered, cherished child (—I learned later that such a child is enviously hated by most women raised not-so-sheltered and not-so cherished by their mother). She captures an expression on my face that I have never seen before but I know well how I feel when I have it. I was feeling at least three things simultaneously.

I was slightly irritated that my mother is yet again turning on me with a camera to take a picture of her precious child. But because I was raised in the Old School of Black motherhood I cannot openly disrespect my mother so I am suppressing that young-man impulse. At the age of 16 I started meditating in what I assumed was the Paramahansa Yogananda style of self realization (my mother was not going to let me hang out with a “cult” so I just read his book in complete isolation). So by the time that photo was taken, 21 or 22, I was relatively connected with what is called in English a “spiritual” part of myself.

But I knew my connection was not traditionally Black American. I was always an outsider. I was both rebellious and embracing of my family’s relationship with Christianity—just like my mother actually. Her photo also captured a sense of self-pity (my chapbook documents this in the ‘self-pity portraits'). My mother turned on me to take the photo like some great moment was taking place. But I felt quite insignificant, staring off into a void just south of Bliss.

Now that I am over two decades older than when that photo was taken (with children of my own) I now understand that my mother was taking a picture of a great moment—a great moment for herself well deserved. Although penniless, her youngest son was a college graduate. He has done everything that was asked of him—never gave her that much trouble—and the LAPD had not molested let alone murdered him. This young man represents years upon years of investment, nurturing and development. He is a product of a Black community that crumbled around him in fragments of crack cocaine. Yes, he is the heir of very impressive, formidable Black men but without the womanhood and the motherhood he would be nothing. That innocent and pure look on his face (that I found out later can be quite despised by some of my sisters in spite of their “wishes” to better people) is genuine—and it was mother that made it so.

So my rebellious book cover for the adolescence of the cool* *is a Blues cover. How many other Black women groomed young men so excellently only to have them overlooked, obscure—some dark cover on some lonesome shelf without a voice? (Again, I am not talking about being overlooked by the Hollywood-fame world; I am talking about that social space that some mistakenly call “community” and mislabel as “intimacy.”) This mother’s photograph sits at the bottom of the dark space of the cover and the photograph itself is “her baby", sitting alone in the backseat of a car with the pitch black of the windows, dotted with only hints of light. It is a typical, fractal African expression: bottom-ness sitting within bottom-ness.

So what does Miles Davis have to do with this? Well, Miles put this Blues thang out called Birth of the Cool. My “arrogant” optimism said my development as a “spiritual” person and as—what we call in English—an artist represented the adolescence of the cool. A collection of poetry from my 20s is really a summary of my adolescence when we get African-conservative about humans in time. So the title of my collection and that bottom-position on the cover of the title itself—in that playful typeface—represents the optimism that is strangely imbued in much of the Blues. (And, by the way, it is because of Amiri Baraka, his Black Arts Movement, that I am so able to freely mix Blues and poetry.)

That playful typeface, by the way (again), reminds me of how my mother used to label Tupperware in the kitchen with a magic marker (my mother’s handwriting was way, way better than what’s expressed in the typeface—so this font is more like me trying to label things with my mother marker). Her handwriting was so energetic, happy and optimistic.

Oh yeah: in typical Bryan fashion, I overlooked the obvious: everything I worked on in school, every formal project I completed as a “gifted” child was first reviewed by my mother. So the Blues here is that because my mother now suffers from dementia she will never be able to review this collection of poetry. I was too busy trying to be an adult while the poems were being written to share them with my mother. And now it’s too late.