Book Review: “The Counter-Revolution of 1776”

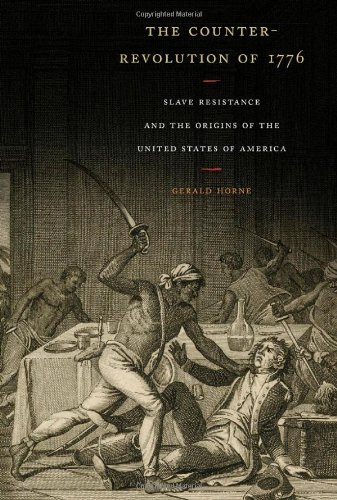

The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America

By Gerald Horne,

New York University Press, 2014

The “moral equivalence of the Founding Fathers”

A review by Dr. T. P. Wilkinson

Since 1976, the bicentennial of the unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) that led to the founding of the United States of America from thirteen originally British colonies, Black History Month has been an officially recognised period—in February—when the descendants of the Founding Fathers acknowledge that the descendants of their slaves also have a history. Also in February, Presidents’ Day—initially George Washington’s birthday but now a combined birthday celebration for Washington and Abraham Lincoln: the Father of the Country and the Great Liberator. The year starts with Martin Luther King Day in January, when some whites and Blacks commemorate the man who was the highlight of the Great March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963—assassinated in 1968 for saying in 1967:

I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today: my own government.

Today the United States is governed with a Black president. And yet as can be seen by the representations of the man occupying the White House, the Black person born in the United States upon whose ancestors—to paraphrase the assassinated Malcolm X—the “rock of Plymouth” fell, still have no history commensurate with the lives taken from them in the establishment of the American Empire.

Maybe this deficit is in some way a blessing. The token historical commemorations dictated by the psychological pacification policies of the US regime are based on the attempt—as in the election campaign of that “son of Africa”—to implicate ordinary Black Americans in the creation of the present regime.

Slaves soon outnumbered Europeans in all of the colonial possessions. Africans soon took notice of this fact and revolted—causing Europeans to invest ever more resources in suppressing the Black labour force. Despite inducements and even impressment, the colonisers failed to lure enough Europeans to the colonies to create a balance of power/terror sufficient to keep slave populations docile.

As James Baldwin so forcefully told William Buckley Jr. and the members of the Cambridge Union in 1965—“From a very literal point of view, the harbours and the ports and the railroads of the country—the economy, especially in the South—could not conceivably be what they are if it had not been (and this is still so) for cheap labour. I am speaking very seriously, and this is not an overstatement: I picked cotton; I carried it to the market; I built the railroads under someone else’s whip for nothing. For nothing.”

There is a significant difference between Baldwin’s claim to have built America and the regime’s rulers’ infamy for founding it. Unfortunately this distinction is not very clear in the popular consciousness because the creation of the USA is always presented as the sum of business transactions performed by the white settler elite. The prevailing historical narrative—across the political spectrum—describes the development (conquest) of the North American continent as one endless series of clever, innovative and even enlightened business deals whose frustration by the archaic practices of the British monarchy were challenged by a declaration adopted and promulgated in 1776.

Gerald Horne’s latest book The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America (NYU Press, 2014) is a continuation of his careful scholarly efforts to correct that historical deficit. Two of his previous books, also reviewed by this author, recover the record of how the United States of America was made by the slave labour of Black Americans and the fanatical determination to preserve this method of enrichment by the white settlers called the Founding Fathers [Negro Comrades of the Crown (2012) and The End of Empires (2009)]. Professor Horne goes beyond those who have finally acknowledged that slavery was fundamental to the economy of the original colonies. He shows that slave resistance forced the settler elite to declare independence from Britain. In doing so he makes Black Americans the drivers of the revolution and white Americans the motor of counter-revolution. Taking Professor Horne’s thesis seriously not only restores the historical dignity of Blacks—more than a month of history—it shows that Africans throughout the Western hemisphere were joined in a liberation struggle whose defeat in mainland North America relied upon the “isolationism” and “exceptionalism” that continue to govern the US regime even today.

The myth of the Mayflower and the first Thanksgiving are still the stories that shape the way US history is understood on both sides of the Atlantic. They are central events in the pageantry used to prove that the Founding Fathers were the precursors of the anti-monarchical revolutions in France and elsewhere. Slavery in the US is thus considered to be a minor defect in the long march of whites toward what are today called “human rights”. This massive distortion has done much to confuse people throughout the world as to what the US regime really represents.

It has made more than one revolutionary leader shake his or her head at the curious relationships the regime has maintained with the white regimes in Africa nearly two centuries later. It has kept millions wondering why the US regime has been a consistent supporter of dictators throughout the world. It has kept US citizens frustrated by the highest rate of Black incarceration in the world, despite the recent election of a Black president.

These inconsistencies have always been defended or excused by the claim that complexities and contradictions in history itself have merely diverted Americans—white Americans—from perfecting the ideals of the Founding Fathers. Professor Horne’s work provides the data necessary to show that these defences are simply false. His careful perusal of the contemporary record reveals that the real principles “held to be self-evident” were those that defined Blacks in the original colonies as property and not as people. The Founding Fathers were first and foremost capitalists who like their descendants believed that freedom was inherent in the right to own property and dispose of it as one sees fit.

To understand this argument it is necessary to go back at least to 1688 and the so-called Glorious Revolution in Britain. This change in the relationship between the British mercantile class and the monarchy catalysed the transformation of British possessions in North America and the Caribbean. It was the first step in the development of what was called “free trade”, the central economic doctrine of the US. Free trade in the 17th century meant the ability of merchants, bankers and landowners to engage in unrestricted profit seeking for private as opposed to state benefit. For the British mercantile class it meant expansion of the slave trade to extract as much wealth as possible from colonies with free labour.

However, the expansion of the slave-based economy caused a serious problem. Slaves soon outnumbered Europeans in all of the colonial possessions. Africans soon took notice of this fact and revolted—causing Europeans to invest ever more resources in suppressing the Black labour force. Despite inducements and even impressment, the colonisers failed to lure enough Europeans to the colonies to create a balance of power/terror sufficient to keep slave populations docile. Here official American history focuses on the failure of revolts in the Caribbean and downplays the impact these revolts had on British colonial policy. In fact, well before 1776, Britain was being forced to consider an end to slavery. At the same time competition among the colonising countries intensified. Wars in Europe arose among the colonisers and these wars became world wars in which colonial possessions changed hands between Spain, France, and Britain. These wars further reduced the profitability of colonial enterprises. By the mid-18th century, every European colonial power was trying to find an accommodation with their Black populations, especially since these wars could not be fought in the colonies without arming them. Black soldiers were not willing to fight for slavery so they had to be freed if they were to bear arms in European wars. As a result Caribbean Blacks were being allowed into the colonial regimes—a process which would transform British possessions forever, except in North America. Colonial rivalry created a class of Blacks who were not only no longer slaves but who were willing to fight in very disciplined regiments against anything resembling slavery—wherever it still prevailed.

As Britain was forced to make concessions in the Caribbean, settlers in North America became increasingly anxious. These concessions induced hard-core slaveholders in colonies like Barbados to abandon their plantations and move to the mainland where British control was beginning to wane. At the same time anti-slavery activism was growing in Britain itself. Professor Horne points to Somersett’s case (Somerset v Lewis of 1772, 98 ER 499), a well-reported British court decision in which the court held that chattel slavery was inconsistent with English common law. The extension of this precedent to the original colonies would have meant the end of slavery and with it the wealth machine driving Yankee merchants and Southern latifundista. Ironically this had followed Britain’s expensive victory in the French and Indian War (Seven Year’s War of 1754–63), after which the British government decreed a limit to territorial expansion on the North American mainland. Professor Horne treats the British victory as a catalyst in the process of secession. On the one hand, Britain freed its mainland colonists from the threat of European competition thus allowing the colonies to expand economically. On the other, it frustrated the colonists by limiting their insatiable demand for indigenous lands to work with slave labour. Horne implies that had the settler regime been forced to remain within the confines agreed by treaty, the rate of Black population growth would have created “Caribbean” conditions. In other words, slave-driven growth would have been stymied as the resistance by the Black population increased.

To avert these consequences the North American colonists had to challenge the mother country. They had to circumvent British prohibition of territorial expansion and ultimately end British jurisdiction to prevent impending abolition of slavery by the Crown. There could be no Caribbean solution.

This is where the sympathy among settler regimes of the 20th century originates. While Britain was being forced to modernise its capitalist system in favour of “free labour”, fanatical Protestant extremists—the core of the Northern settler elite—were opportunistically abandoning their institutionalised discrimination against Catholics and lower order Europeans like the Irish and Scots (later also extended to despised Southern Europeans) to compose a race-based regime that could expand to fill the still to be conquered territories and keep the slave population in check. The Somerset case was the 18th century equivalent of Harold Macmillan’s 1960 “Winds of Change” speech. Hendrik Verwoerd’s Afrikaner republic and Ian Smith’s Rhodesian National Front were by no means distortions of the American ideal which both claimed to follow in their attempts to inaugurate explicitly white states based on the exploitation of African labour. Both regimes even made concerted efforts to replicate the US model of privileged immigration for Europeans in the hopes of dominating Black majorities—albeit unsuccessfully.

The obvious objection to Professor Horne’s thesis is that it is anachronistic. By applying current models of historical analysis to 17th and 18th century North America, he could be accused of imputing intentions to the Founding Fathers based on current definitions of human rights. Thomas Jefferson is often held out as a fig leaf. His supposed attitude toward slavery is considered by official American history as an alibi for the “defective” failure to include Blacks in the definition of equality. According to this view—still the mainstream interpretation—the demands of the “revolution” required a compromise between Northern colonies that were willing to abolish the slave trade and powerful Southern slaveholders. In other words, the race-based regime founded in 1776 was merely flawed because it would otherwise have been impossible for the colonists to continue the march toward freedom if they could not unite against Britain. This argument is echoed in later events like the Missouri Compromise.

Another principled objection from official history—again across the political spectrum—is that the final abolition of slavery in 1865 exonerated the American pageant. It is hence impossible to attribute to the Founding Fathers motives which they could not have had at the time—given the prevalence of slavery throughout the Western hemisphere.

The Counter-Revolution of 1776 successfully rebuts both arguments. First, it documents thoroughly that the key players in the 1776 UDI were almost without exception major slaveholders or slave traders. For instance, John Hancock was Boston’s largest slaveholder—perhaps the real reason for his ostentatiously large signature on the Declaration. James Madison was a staunch defender of slavery—going so far as to introduce the 2d amendment to the US Constitution in order to secure the autonomy of state slave patrols. Copious correspondence demonstrates that the Yankee and Southern oligarchs knew that Britain was being forced to abolish slavery. That would have been financial ruin for the merchants and plantation owners. Even more serious was their fear that Blacks would claim their rights with vengeance as they had been doing in the Caribbean and in the border wars between Florida and South Carolina/ Georgia. They made no secret of either.

Moreover, the official history relies on an assumption that Blacks in North America were essentially docile and unaware of either their humanity or the struggle waged among white elites over their status. If Blacks were passive property, then the entire struggle was only between colonists and the mother country. This has never been true. Despite the alienation and deliberate attempts to destroy cultural cohesion among the slave population, there was never a period when Blacks did not organise resistance. That resistance was successful to the extent that it persisted throughout all of Britain’s colonial possessions. Attempts by Caribbean plantation owners to pacify their slaves, by deporting unruly ones to other colonies, only served to expand the consciousness of Blacks as to what was really happening. The recruitment of slaves to fight European wars not only produced cadre of seasoned warriors but discredited efforts by whites to prove their superiority.

Jean-Paul Sartre argued at length that the French Revolution as past is inaccessible. Thus there is no point in writing history “as if”. Gerald Horne does not propose such a history. Instead he is quite consistent with Sartre when he analyses the data available for constructing the past. His is not an appeal for some newfound sense of guilt that white America is based on a lie—even if it is. At the same time his analysis is quite consistent with those traditionalists who constantly rave about strict construction and the intentions of the Founders. The Federalists—then as today—assert unabashedly that they were and are guided by the firm principles and intentions of the Olympian slavocracy that founded the US. If they are right and the US regime is to be judged by the traditions maintained today as the foundation of the republic, then Gerald Horne has merely provided the full brief. If the Founding Fathers intended to create the republic that is today the paragon of capitalism and the “greatest purveyor of violence in the world” (which in terms of weapons exports and military expenditure it still certainly is), then the Founding Fathers certainly intended a counter-revolution.

When the dead US president, now beatified, spoke to the Conservative Political Action Conference two hundred ten years later he said:

They are our brothers, these freedom fighters, and we owe them our help. I've spoken recently of the freedom fighters of Nicaragua. You know the truth about them. You know who they're fighting and why. They are the moral equal of our Founding Fathers and the brave men and women of the French Resistance. We cannot turn away from them, for the struggle here is not right versus left; it is right versus wrong.

He was criticised severely by liberal and left-liberal opponents of US Latin America policy, supporters of the Sandinista Front government in Managua and aid organisations in the US caring for the refugees who had fled the US-sponsored and managed counter-insurgency and terror wars in the region. (It was estimated that approximately 15-20 per cent of the Salvadoran population was either killed or forced into exile by “freedom fighters”.) Since Ronald Reagan had long been dismissed as senile at best and a lunatic at worst, remarks like these were treated as offensive but more or less right wing boilerplate. Mr Reagan remained objectionable but the outrage over his statement arose from the belief held from centre to left that he had maligned the Founding Fathers and soiled the original ideals of the USA by associating them with CIA-trained and funded terrorist bands.

As Gerald Horne, explains in The Counter–Revolution of 1776, this indignation is seriously misplaced. In fact, Ronald Reagan should have been taken at his word since what he said was historically accurate. Unfortunately most critics of the Reagan regime, its predecessors and successors either do not know or do not understand the actual historical basis for the war of independence from Great Britain started by the British colonial settler elite in 1776. As Gerald Horne notes:

Jean-Paul Sartre argued at length that the French Revolution as past is inaccessible. Thus there is no point in writing history “as if”. Gerald Horne does not propose such a history. Instead he is quite consistent with Sartre when he analyses the data available for constructing the past.

Ironically, the US in a sense has emulated today’s Cuba insofar as the operative slogan seems to be “within the Revolution everything, against the Revolution nothing.” In other words, one can quarrel about the destiny of the republic but—generally—not the eternal verity it is said to have created. Of course, left-wing republicans tend to emphasize the role of less grand Europeans in 1776 (those not of the left wing tend to stress the role of the Olympian Founding Fathers). Some of these historians tend to see the plight of Africans as the “original sin” of the republic (which begs the question of dispossession of the indigenous). In any case, I suggest in the concluding pages of this book, the left wing’s misestimating of the founding is of a piece with their misestimating of the present: this includes a reluctance to theorize or historicize the hegemony of conservatism among the Euro-American majority—an overestimation of the strength of the left wing among this same majority—which has meant difficulty in construction of the kind of global movement that has been essential in rescuing Africans particularly from the violent depredations that have inhered in the republic.

© 2012 Dr. Patrick Wilkinson, Institute for Advanced Cultural Studies—Europe