lines in the rasx context

1990’s

The 1990s were my post-college, Bush Sr., poverty years. I could not find a decent job upon graduation so buying new CDs was definitely out of the question. I did not feel like I was missing much. Much of the arts and entertainment of this decade (and beyond), I file under the title “Hey, It’s Better than Nothing.” This means that most of the music coming out of the 1990s was uninspired business deals led by entertainment lawyers who were preoccupied with composing contracts to re-release stuff that was on vinyl in the new compact disk, the Redbook CD Audio format. I am sure that the 1990s will be remembered as the “file-sharing” era of lawyers, creating legal documents for the sale of CDs from large, impersonal corporations.

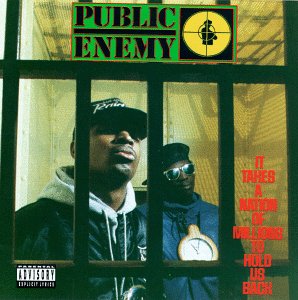

Public Enemy was one of the few acts of the 90s that deserved my new/used-CD-buying attention, featuring the Black man Chuck D and the neo-minstrel Flavor Flav. Eventually this rap group was yanked out of the spotlight by the Jewish Defense League and others—as they turned into self-described, comic-book super-heroes of the Nation of Islam—but, before they did, they laid down a classic, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back. This album features my all-time favorite rhythm rhyme “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos.” This was the song that convinced me that hip-hop music could be a literate art form as well as party-jam fodder (and yes: I am aware of KRS1, Paris and that guy from the Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy):

When I first heard this song in college, I could only catch little bits of the lyrics. I thought for sure that these brothers were straight talking about the 1971 uprising in the Attica Correctional Facility near Buffalo New York. I thought I had found some seriously educated griots with the ear of the masses—and this why the FBI was tapping their telephone. I was wrong but the work is still strong. The opinion here is that “Black Steel” intermingles the real-life story of a real-life hero Muhammad Ali, his refusal to enlist in military service in 1967, with all the fantasies many African American male prisoners have ever had about breaking out of prison. It was this tendency to fantasize that limited the power of Public Enemy and I know the fans out there are hissing and booing at me for writing this—but I know we can do better—not just “better than nothing.”

But wait before you treat me like a step child!

Let me tell you why they got me on file.

Because I give you what you lack

—upright and exact.

Our status is the saddest—I don’t care where you at, “black.”

These lines from “Louder Than a Bomb” on It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back could very well be the rebuttal to my previous comments. Chuck D is saying that his writing style is very loose and free form—he even compared it to the improvisational style of John Coltrane. And the last line is a very important line. I believe that he trying to remind the careful listener that Africans in America definitely have made great individual achievements but, as a collective, we still totally suck. We’re doing great collectively compared to abject slavery—but if we compare ourselves to the communities and civilizations in Africa before the time of Columbus, we should find some serious moral/spiritual deficits.

Chuck D asks in “Bring the Noise” on It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, “Bass! How low can you go? Death row? What a brother know’?” The decade of the 90’s answered by creating Suge Knight’s Death Row Records and the young people started hanging with the dogs instead of the gorillas with a pistol grip pump on the lap at all times.

|

Words of a feather

All flock together, Going ’round and ’round. The soul is astral traveling, Watching human motion —Wasting thy seed upon the ground. |

|

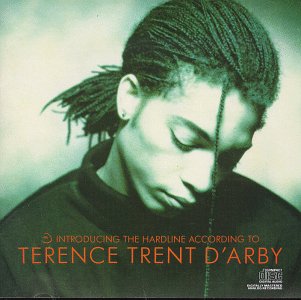

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, a young, AWOL, U.S. soldier running out of Germany took England by storm. In a daring attempt to be a literary James Brown, Terence Trent D’arby reveals his Christian roots being the boxing son of a preacher man with the soulful and rueful “If You All Get to Heaven” on one of my favorite 90s albums (by the U.S. release date) Introducing the Hardline According to Terence Trent D’Arby.

TTD strikes me as a welter-weight version of Basquiat, telling again that tragic story of yet another intelligent African-American male “forced” to sell himself as meat instead of spirit. He had to run away across the Atlantic to earn some semblance of recognition and respect—and money. And, speaking of money, I am very proud to say that one of TTDs session musicians has been Muata25, interviewed right here in the kinté space!

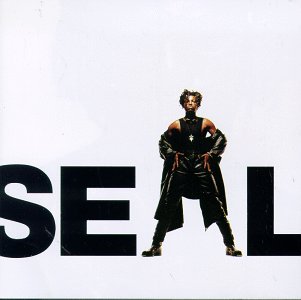

Seal Henry Samuel was born across the Atlantic, in England in 1963—but he had to run away to Asia before making it big back home in England:

His 1991 debut album Seal is as close to hard-core “Christian rock” as I am going to get. What his publicist(s) would insist is “new age mysticism” is, to my ear, very Judeo-Christian Biblical. This line from the song “Crazy” is a wonderful way to approach the concept of heaven without saying the word “heaven.”

Another way he approaches “heaven” is to call it a “Future Love Paradise”:

You would know from their faces

There were kings and queens

Followed by princes and princesses

There were future power people

From the loved to the loveless

Shining a light ‘cause they wanted it seen

Well there were cries of why

Followed by cries of why not

Can I

Reach out for you if that feels good to me

And the riders will not stop us

‘Cause the only love they’ll find is paradise

No the riders will not stop us

‘Cause the only love they’ll find is paradise

Paradise yeah

Don’t you know that racism in among future kings

Can only lead to no good

to no good

Besides your sons and daughters

already know how that feels

One day (One day)

All the queens will gather round

Spreading love and unity so it can be found

Well then all the riders say it’s all to do with drugs

Well inject me

With your love

Inject me with your love alright And the riders will not stop us

‘Cause the only drug they’ll find is paradise

Seal’s first album was, I understand, criticized for being too idealistic or naïve in spirit (and he dutifully tried to be “more realistic” on his next releases). And I don’t particularly find these lyrics listed above very poetic. But I can’t pass up these relatively unique references to targets of racism. “The riders” I immediately see as racist police officers patrolling in their cruisers—or the original racists riders, the Klansmen of the old North American South. To think that one day, a “future power” community of African Queens will “inject” me with love is something I just can’t pass up.

I also have a deep suspicion that this song, “Future Love Paradise” is a “sequel song,” following up the Stevie Wonder classic “Pastime Paradise” from his masterpiece Songs in the Key of Life. Not quite sure but it better than nothing.

The New Millennium of MP3s

Yawn. Hey, it was Pink Floyd that perfected the “concept album”: that an entire body of released material is one whole expression meant to be listened to in its entirety like watching a motion picture. It was quite a naïve assumption on my part to expect that every release from every musical artist would intend to uphold this sense of unity—let alone be filled with poetic lyrics. What is more natural is fragmentation, bits and pieces—entropic musical experiences. My new relationship with MP3s represents this more “natural” way experiencing music.

When I was a teenager, I was quite engaged by David Bowie’s world travels condensed into a single album (e.g. Lodger). He would travel the world and bring me the music he liked into an eclectic mix for my listening pleasure. Then came the CD, which allowed the artists that inspired David Bowie to make their own albums. I don’t think we would have record companies like Peter Gabriel’s Real World Records without the invention of the compact disk. Nevertheless, the total cost of ownership of all these CDs are still governed by those lawyers and corporations aforementioned. This makes prices high and broadcast radio play low. So how do I find out about all of these artists all over the world? How can I explore their sound, hear their voice?

Enter the MP3. Now everything is mixed up. My MP3 files jump around from decade to decade, from genre to genre. Now, the lines in the rasx context appear without regard to contemporary pop music sensations stimulating the world right about now. I’m long gone, man. I’m an outlaw. Many will say that I am a thief. According to recent news articles. My ethnic background fits the profile: a thieving, Black male with broadband access. But the story that seems so hard to believe by more savvy, right-thinking people is true for me as well: I buy the album if I like more than three songs on one release.

Simultaneously, I have several hundred compact disks (mostly purchased in the late 1990s). Many of these disks have just one or two songs on them that I like. I “rip” those songs off the CD into MP3 format and get rid of the CD in order to save space. So many of the MP3s I have come from CDs previously purchased. Don’t you believe me? Or do you just profile me? Additionally, I have CDs that, over the years, have become damaged and cannot play in my car. So it would be wise to “burn” copies of these CDs before the damage gets worse—again another legitimate reason to be branded a criminal.

What is definitely criminal is to download music and listen and listen to a song without knowing anything about the artist(s) behind the work. I have made the effort to fill out all of the ID3 tag information in my MP3 files so players like Winamp 2.x can look up the artist in the Muze Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Many of these artists were robbed by record companies in exchange for the false promise of fame. So the least I can do is to read about these folks. There is often more poetry in their lives than in the lyrics.